Recommendation 2, Strategy 2:

Increase Functional Bed Capacity – Create a Forensic Mental Health Roadmap

Strategy 2: Reduce forensic hospitalizations by creating a roadmap that provides alternatives to ASH for competency restoration. Key strategies include:

Creating alternative mental health treatment options to refer people from the

legal system:Prior to arrest, by health-driven crisis management into treatment

rather than incarceration;Following arrest, within the legal system through mechanisms such

as civil commitment and assisted outpatient treatment to refer individuals

into treatment rather than incarceration;

Referring people experiencing acute mental health needs to the least restrictive clinical and legal environments necessary to provide care, avoid arrest and incarceration, and safely and efficiently resolve any necessary criminal charges;

Establishing a consistent, best evidence forensic assessment process that responds quickly to court requests and working with the judiciary to help the courts implement best practices;

Initiating mental health evaluation, peer support and treatment as quickly as possible, even in jail if necessary, rather than waiting for state hospital resources to become available;

Expanding competency restoration capabilities outside the state hospital; and

Referring Class A nonviolent and all Class B misdemeanants to appropriate community-based treatment rather than prosecution (and hospitalization) whenever possible.

“2019 prevalence estimates found that 1.8 million people with a mental illness are arrested and booked annually.”

Increasing the functional bed capacity of the new ASH requires changes in how the mental health and legal systems currently intersect. As a reminder, functional bed capacity refers to optimizing the use of the hospital for what it was designed to provide (i.e., acute and subacute inpatient care) within a broader continuum of emergency, inpatient, and community-based clinical care. People often enter the mental health care system when they experience a crisis and law enforcement is called to assist; at times these situations lead to arrest and criminal prosecution of the person experiencing mental illness. The occurrence of this legal and clinical intersection is common. For example, 2019 prevalence estimates found that 1.8 million people with a mental illness are arrested and booked annually (Leifman, 2019). The individual is then thrust into the intersection of the treatment and legal systems with adjudication of competency at times leading to unnecessary hospitalization rather than community-based care settings.

“Expanding health-driven rather than police-driven responses to acute mental health conditions across the ASH service area will be important”

The best response is to avoid arrest and incarceration entirely, and the new best practice multi-disciplinary response team (MDRT) framework being deployed in Travis County this year offers a solution long-term for reducing the flow of people into the legal system, based on its success in other Texas communities (Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute). Expanding health-driven rather than police-driven responses to acute mental health conditions across the ASH service area will be important, and legislation (HB 1050) has been filed to evaluate the availability, outcomes, and efficacy of strategies to expand MDRT and tailor it to the needs of diverse communities (including rural communities).

Current Forensic and Mental Health Intersection

The long-term consequences of criminal prosecution are significant; consequently, the United States Constitution prohibits a person from facing prosecution if they lack the capacity to understand the proceedings against them or assist their attorney in preparing a defense (Drope v. Missouri, 420 US 162, 171 (1975). To ensure constitutional due process, when there is a suggestion that a criminal defendant lacks that capacity, they are evaluated and may be deemed “incompetent to stand trial.” In Texas, the procedures that define how to establish incompetent to stand trial are provided in Article 46B in the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure. This code applies to both misdemeanor and felony charges. Article 46B defines a person incompetent to stand trial if the person does not have: 1) sufficient present ability to consult with an attorney with a reasonable degree of rational understanding; or 2) a rational and factual understanding of the proceedings against the person. The determination of whether these conditions are present is made by a qualified psychiatrist or psychologist (under Article 46B.022) after the issue of incompetence has been raised by either party or the court on its own motion. The delay between the court’s request for an evaluation and the completion of such evaluation can be significant at times, especially in counties that lack access to a forensic evaluator. The intent of Article 46B is to protect people from an unconstitutional prosecution and punishment when mental health issues preclude a fair trial. The proliferation of individuals with serious mental illness facing criminal prosecution has contributed to a marked backlog within the public psychiatric hospital system and calls for an increased need for more alternatives in less restrictive (and resource limited) settings.

“The proliferation of individuals with serious mental illness facing criminal prosecution has contributed to a marked backlog within the public psychiatric hospital system and calls for an increased need for more alternatives in less restrictive (and resource limited) settings.”

Once a person is adjudicated incompetent to stand trial, if the criminal charges are not dismissed by the prosecution, the court commits them to a process called “competency restoration.” Competency restoration occurs in one of the three settings: jail, outpatient clinics, or a hospital. Commonly in Texas, competency restoration occurs in a hospital setting due to limited outpatient and jail-based competency restoration programs and alternative residential treatment and housing options (please see Housing Options strategy). Moreover, with the historical perception of hospitalization being the only option, these alternative programs may not be utilized to the full extent possible. Both clinical and legal professionals strive to improve a person’s mental health and ensure constitutional due process if criminal prosecution is pursued by the State. The overlap of clinical need and legal competency restoration is typically considered jointly; however clinical improvement does not guarantee competency restoration, and conversely, restored competency does not necessarily mean clinical concerns are resolved. Several non-clinical factors, including age, criminal history, and degree of violence significantly impact the likelihood of competency restoration in addition to clinical improvement (Zapf, 2011). Consequently, it remains critical to consider separate approaches to resolution of legal charges AND optimal clinical care, with a goal to manage each and their intersection optimally within the least restrictive setting possible.

The percentage of people committed by the court for competency restoration nationally and at ASH has steadily increased. This increase in commitments for competency restoration is decreasing available space for civil commitments (Figure 8). Civil commitment is a process for people who are unable to care for themselves or are an imminent risk to themselves or others, and are involuntarily referred for inpatient psychiatric care. The length of stay of forensic admissions is longer than their civil counterparts due at least in part to the complexities surrounding suboptimal processes in the intersection of these two systems. This difference highlights that individuals in competency restoration regularly remain hospitalized beyond the time that their clinical acuity requires inpatient care. Consequently, this situation represents a suboptimal use of an expensive and limited acute care resource, thereby decreasing the functional capacity of the hospital and leading to fewer people being served (Figure 8).

“The percentage of people committed by the court for competency restoration nationally and at ASH has steadily increased.”

Part of the issue causing the decrease in functional capacity is that the potential length of commitments of persons found incompetent to stand trial. An initial commitment to determine whether the person’s competency can be restored is for a maximum of 60 days for misdemeanors and 120 days for felonies, with one extension of 60 days available, whether commitment for restoration is to inpatient, jail-based or outpatient competency restoration programs. These limitations mean that a defendant completes the maximum statutorily-defined commitment period for competency restoration at ASH in a relatively reasonable time (120 days for misdemeanors, including the initial 60-day commitment and one 60-day extension; and 180 days for felonies, including the original 120-day commitment and an extension of 60 days). However, if the defendant remains incompetent to stand trial, further mandatory treatment, whether inpatient or outpatient, may be indicated and the lengths of time in the hospital expand significantly, even though many of these individuals may no longer require inpatient-level services for ongoing care (if other options are available).

To address this concern:

The prosecution can elect to dismiss the case completely, which would result in

Release of the individual to the community or

Transfer to probate court for a civil commitment under Subtitle C, Title 7,

Health and Safety Code if civil commitment criteria is met, OR

Charges may remain pending, with the criminal court maintaining jurisdiction over the case and civilly committing the individual under Subtitle C, Title 7 Health and Safety Code if civil commitment criteria is met.

Civil commitments require the prosecution to file a petition with two certified medical examinations setting forth the civil commitment criteria met by the defendant. The physicians who complete the examinations are generally appointed by the court and not a member of the person’s clinical treatment team; this break in clinical assessment may contribute to miscommunication or misinformation guiding subsequent decisions. It also limits how the hospital participates in disposition decisions.

“...extraordinarily long commitment periods are permitted by law.”

A civil commitment may be renewed annually for periods of up to 1 year at a time, with the exception that it cannot exceed the maximum sentence for the underlying criminal offense. This means that extraordinarily long commitment periods are permitted by law. For example, a person charged and indicted for aggravated assault with a deadly weapon, whose case has not been dismissed, can be legally held in the hospital up to 20 years – the maximum jail sentence for such an offense – so long as civil commitment criteria are met and the defendant remains incompetent. When the decision is made to extend a person’s civil commitment and continue the hospitalization, the determination is made by a criminal court judge and not a physician providing clinical care; this approach may contribute to a de facto long-term punishment for someone with mental illness without a trial.

Figure 9 illustrates the dramatic five-year increase in forensic bed days on extended commitments at ASH. It should be noted that research has shown competency restoration past the initial 60- or 90-day commitment becomes increasingly unlikely (Zapf, 2011; Gillis 2016); moreover, it is rare to have an individual whose illness requires inpatient level of care for such an extended period. Consequently, there are diminishing returns to continued use of hospital resources in these circumstances. The combination of an increasing forensic population and increasing extensions limits the number of people ASH is able to serve, thereby creating inefficient and suboptimal use of expensive and limited acute care hospital capacity. This problem is compounded by the general lack of residential treatment and other possible housing options in most Texas communities. In addition, due to limited resources, community competency restoration facilities are not designed to receive extended commitments which means there are limited community alternatives to the hospital setting, creating an over reliance on a hospital that is already fully utilized and has an ongoing waitlist for admission.

“...research has shown competency restoration past the initial 60- or 90-day commitment becomes increasingly unlikely...”

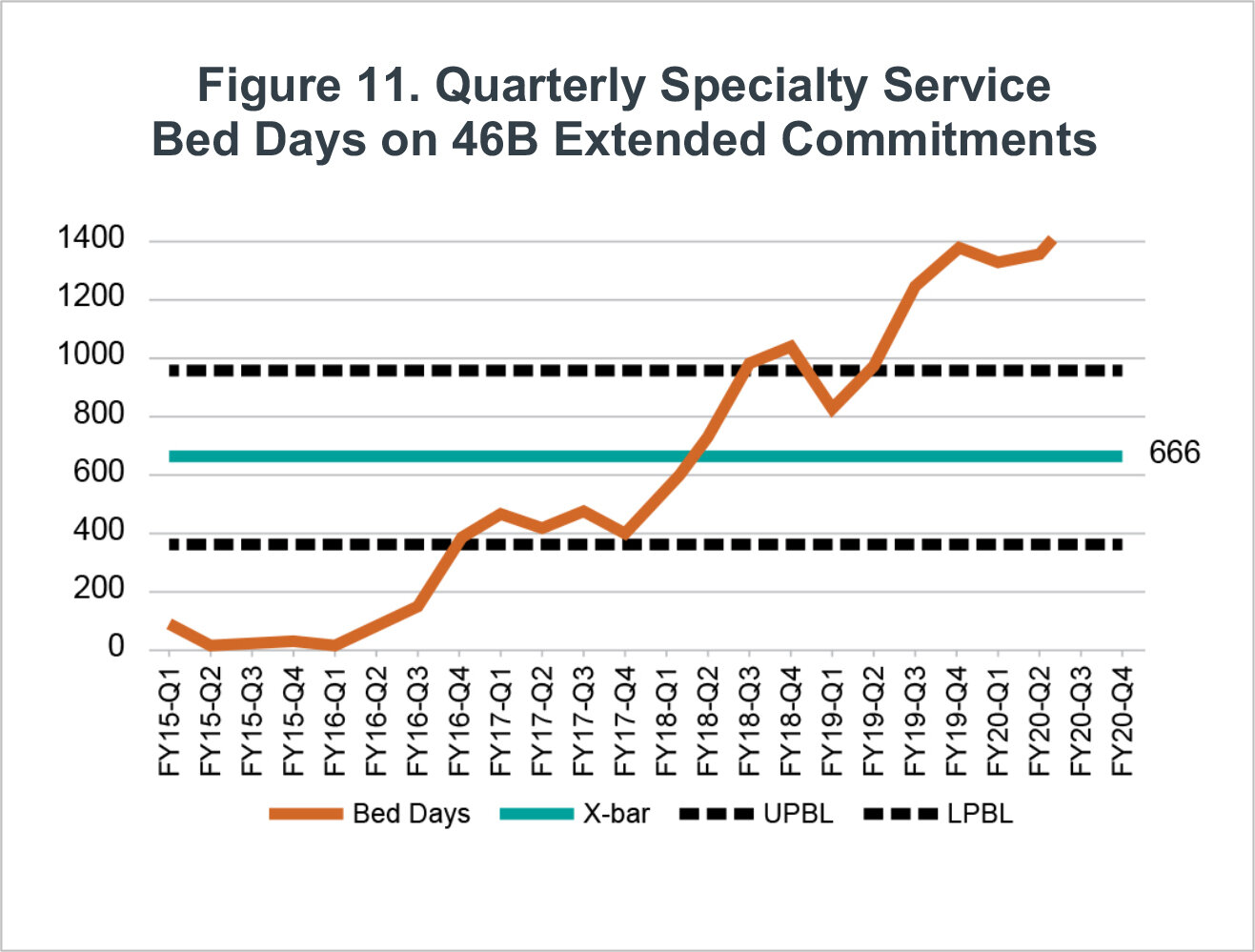

Figures 10 and 11 illustrate demand for specialty services for individuals served by ASH with co-occurring conditions such as intellectual disabilities. As with the general ASH population, the graphs demonstrate a rise in bed days for 46B initial and extended commitments. The downturn in FY20-Q2, reflects the impact of COVID-19 that decreased capacity of ASH as the hospital provided space for isolation and safety measures (although increased the waitlists). It is expected once operations return to a more pre-COVID status that increasing percentages of extended commitment will resume unless changes occur in this intersection between the legal and mental health care systems.

“…we can then provide more care in the right place at the right time for more Texas citizens.”

ASH beds being used for extended commitments that do not require inpatient level clinical care create delays for other individuals, civil or forensic, who require this level of clinical support. The backlog often traps individuals in alternative venues not adequately designed to manage either their clinical or legal needs, thereby inefficiently using resources and increasing overall costs of the competency restoration process. For example, as described in our previous report (ASH Report), a typical competency restoration admission at ASH costs approximately $45,000 based on a daily cost of $752 (including benefits and estimated overhead). Adding an extension for 60 more days incurs an additional $45,000 in cost to the state that may be unnecessary in many circumstances. This total expense is in addition to costs related to a person’s time on the waitlist in jail, which can be excessive but preventable through outpatient alternatives. Previous work from the ASH Redesign report found that a mixed competency restoration initiative including a rapid stabilization (short) inpatient stay, support from a Forensic Assertive Community Treatment (FACT) and intensive outpatient care costs an estimated $19,625, less than half of hospitalization costs alone in the current typical approach and significantly less than an extended commitment approach. There are clearly less expensive alternatives to provide a person a more meaningful experience within their community than the status quo. If these can be created and adopted, we can then provide more care in the right place at the right time for more Texas citizens.

As previously discussed, Travis County is the top referring county to ASH. The snapshot of the July 2020 waitlist (section Overview and Background) found 45 people under a 46B commitment from Travis County waiting for a bed at ASH. The average length of time between when a hospital received an order and the person was admitted in calendar year (CY) 2019 was 31 days, but some waited much longer. Moreover, these calculations do not include the amount of time an individual waited before being evaluated or the hospital was notified of an order. These delays in jail represent suboptimal management of these individual’s clinical needs and legal resources highlighting the importance of creating a new roadmap for these processes as proposed. As mentioned previously, identifying ways to work with community mental health providers, namely the local mental health authorities, to intervene earlier in the process to either avoid arrest or intercept clients prior to prosecution could alleviate some of the later pressure to hospitalize individuals after they arrive in court.

Multiple Efforts Aligned

There are several efforts across Texas seeking solutions to the overly-complex entanglement of the legal and mental health systems. The Hogg Foundation for Mental Health convened leaders from several statewide and regional projects to discuss their efforts and recommendations for managing the increasing forensic population. The groups included the Joint Committee on Access and Forensic Services (JCAFS), San Antonio State Hospital (SASH) Redesign, Texas Judicial Commission on Mental Health (JCMH), and ASH Redesign. Appendix 7 provides details of the conversation. The discussion raised consensus of top priorities to implement that included:

Establishing a statewide Office of Forensic Services to develop and implement a consistent strategic plan to eliminate or shorten unnecessary forensic hospitalizations;

Using data sharing to enhance collaborations among stakeholders within the legal

and mental health systems, including partnering with Texas’ medical schools for

this work; andIncreasing alternative treatment and competency restoration options other than hospitalization throughout the state.

Nationally, similar discussions are occurring. We can learn from successes from states that have made effective changes within their forensic mental health pathways. The Just Well: Rethinking How States Approach Competency to Stand Trial report shares ten strategies already in operation across the country that may serve as models (Appendix 8). The ASH Redesign team and the consensus from the Hogg Foundation work align with the following strategies listed by the Just Well report:

Convene diverse stakeholders to develop a shared understanding of the current competency to stand trial (CST) process.

Examine system data and information to pinpoint areas for improvement.

Expand opportunities for referral to treatment at all points in the legal system, including after competency has been restored.

Conduct evaluations and restoration in the community, whenever possible.

Forensic Roadmap

With these considerations in mind, the ASH Redesign team will develop a regional roadmap with partners and stakeholders to reduce unnecessary forensic hospitalizations by identifying opportunities and solutions to provide mental health care for people engaged with the legal system in the least restrictive setting possible. The roadmap will spotlight gaps and areas for improvement within the system that will guide us to implement pilot programs to test the roadmap programs’ ability to increase the new ASH’s functional bed capacity. It will work within the context of HHSC and other statewide planning efforts to reduce duplication while potentially offering opportunities to test new models of managing the complex intersection of the legal and clinical mental health intersections.

To build the roadmap, data gathering is needed to understand pathways used within the mental health and legal system. A strategy to gather these data is to create a consortium with the LMHAs, county jails, probation and parole, and municipal law enforcement of the ASH service area, and to develop a collaborative process to monitor how people move through the two systems. Medical schools may be able to assist with data management and analytics, serving as so-called ‘honest data brokers’ among entities. This process will provide insight to the most frequent pathways leading to admittance to ASH. In addition to understanding the pathways, the team will examine ways to provide quicker access to the initial evaluation, peer support, and treatment to stabilize individuals clinically as rapidly as possible. In conjunction with these efforts, corresponding least restrictive settings for competency restoration will be identified. A potential approach toward this goal is a partnership with a medical school(s) or other providers to design a team to quickly intervene as soon as (or perhaps before) a person is booked into jail. This strategy is one that can be accomplished in person for counties close to available providers, but may also be feasible using telemedicine to provide support to rural counties that lack the necessary mental health workforce.

As part of the roadmap, we will examine currently available resources for competency restoration within the ASH service area. In the previous ASH Redesign report, 18% of the ASH 38 core counties reported having outpatient competency restoration programs provided by the LMHA, although how well utilized these services are is uncertain. It is important to incorporate additional public programs that have been contracted with HHSC as the State works to increase outpatient competency restoration capacity. Creating a map of these services will clarify which counties may need more outpatient competency support and represents a critical first step toward understanding gaps and identifying potential regional solutions.

“It is important to incorporate additional public programs that have been contracted with HHSC as the State works to increase outpatient competency restoration capacity.”

Pilot programs will be implemented as gaps and needs are discovered through the roadmap development process in order to test new models of service provision. For example, there is an opportunity to decrease hospital referrals for nonviolent Class A and potentially all Class B misdemeanants to a more appropriate community-based treatment instead of prosecution. For misdemeanants in which prosecution remains necessary, it may still be preferred to refer them to a community-based competency restoration program and intensive outpatient care when clinically appropriate. By doing so, ASH functional bed capacity will be increased allowing waitlists to be reduced. When hospitalization is clinically indicated, instead of Article 46B referral for care, the courts could opt for a civil hospital commitment while managing the legal charges separately (i.e., return to court after hospitalization or dropping non-violent charges). This approach would decrease the number of people waiting in jail for a hospital bed, eliminate unnecessary court-ordered 60-day commitments and extensions, and create more efficient use of ASH capacity and the courts. Mapping these potential strategies will guide the system to areas for improvement. Implementing pilots around these strategies will identify best practices and how to create a more functional hospital for the new ASH (and other service areas around the state, by extension).

Other State and Local Models

Other state and counties are also improving their mental health and legal system intersections. For example, Miami-Dade County’s jail serves as the largest psychiatric facility in Florida. In response to the significant number of inmates in jail needing mental health services, the Eleventh Judicial Circuit Criminal Mental Health Project (CMHP) was developed by Judge Leifman to remedy the growing forensic population and criminalization of mental illness. CMPH created four programs: 1) pre-booking and 2) post-booking jail diversion programs, 3) the Miami-Dade Forensic Alternative Center (MD-FAC) program, and 4) the SOAR entitlement program. CMPH’s pre-booking program includes Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) training for law enforcement and the post-booking program includes both misdemeanor and felony referral programs (Appendix 9). The MD-FAC pilot was established to show feasibility to refer people deemed incompetent to stand trial or guilty by reason of insanity from state forensic hospitals to community-based treatment and forensic services (Leifman, 2019). A fourth initiative is the SOAR Entitlement Program that uses the SOAR (SSI/SSDI, Outreach, Access and Recovery) model to expedite the process for people with mental illness to receive available social security benefits if they are experiencing homelessness (Leifman, 2019). CMPH is regarded nationally as a success and a program to replicate to reduce the criminalization of mental illness, decrease costs in counties and states, and provide care in the community rather than jail. The combination of these programs led to significant improvements in managing the growing forensic population with mental illness. For example, the CMPH model has shown that people in the misdemeanor post-booking program decreased their recidivism rates from 75% to 25% annually (Boatwright, 2018). Additionally, the programs achieved an annual $17M cost avoidance in jail days from pre-booking crisis referrals to community crisis stabilization, and approximately a 32% decrease in cost serving people in the MD-FAC instead of state forensic treatment facilities. Finally, the expedited process of SOAR provides benefits in 40 days in comparison to the usual 9 – 12 months (Leifman, 2019). The Miami-Dade Model is for a dense urban setting, but aspects may be translatable to other settings.

“The combination of these programs led to significant improvements in managing the growing forensic population with mental illness.”

Typically, rural counties must develop their mental health support differently from urban counties. In a rural setting, the necessary workforce is scarce, county funding is often limited especially for mental health services, and there may be more stigma around mental illness (Stewart, 2015). Many rural counties are joining efforts with neighboring counties to support mental health needs and a growing forensic mental health population. A widely used solution for communities is to implement telehealth services to expand rural county access to care providers; telehealth can be incorporated into crisis and diversion programs to help manage individuals prior to arrest or prosecution. A national review of 2010 – 2017 Medicaid data reported a 425% increase of telemedicine for rural beneficiaries diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder (Patel et al, 2020). Extending telehealth into county jails is also beginning and, with the support of grants, some counties have created this infrastructure. For example, the Correctional Telepsychology Clinic (CTC) from the University of Mississippi Medical Center is a pilot model of multidisciplinary teams offering telehealth to the rural county legal system involved population (Batastini et al, 2020). This particular pilot is in early stages, but one to track for potential use in Texas.

Many states are implementing Certified Behavioral Health Clinics (CCBHC) to address unmet mental and substance use needs. The CCBHC program was established from the bipartisan Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014 to create a new Medicaid provider type to expand access to mental health and substance use disorder treatment for vulnerable populations (National Council for Behavioral Health, 2020). The CCBHC program began with an 8-state demonstration program that was funded through a Medicaid payment model. Programs outside of the 8-state demonstration are funded through grants. In order to qualify as a CCBHC, organizations must expand their array of services, a key aspect of which is the inclusion of 24/7 crisis response. They also must increase collaborations and partnerships in order to serve all individuals needing services regardless of a person’s ability to pay (National Council for Behavioral Health, 2020). There are a total of thirty-three states operating CCBHCs, and Texas is one of these with a total of 19 certified sites (Texas CCBHC). Of the 19 Texas CCBHCs sites, there are 3 within the ASH service area. Partnerships with law enforcement that were created through the CCBHC model are providing decreases in recidivism, lower jail costs, and decreased travel time for officers. The National Council for Behavioral Health’s CCBHC impact report provided an example of the success of this approach from Oregon’s rural Klamath County, which saved $2.5 million in prison costs through increased community services and decreasing recidivism (2020). As these programs prove successful, expanding them in Texas might increase access and partnerships to serve rural communities.

Improvements in forensic mental health and competency restoration processes must be supported at a state level, since both local and state resources typically are necessary. They must occur within the context of other continuum of care improvements, e.g., increased capacity of non-hospital residential treatment and other housing options. Using established best-practices in conjunction with reviewing the current system and collaborating with other groups, we will create a forensic roadmap to advance the forensic mental health system in the ASH service area and thereby increase the functional bed capacity of the facility.

Recommendation Summary:

Forensic Roadmap

• The percentage of ASH admissions for people with 46B commitments are increasing rapidly, displacing other hospital uses.

• Hospital beds encumbered by competency restoration exhibit increased lengths of stay, decreasing the functional capacity of ASH and other state hospitals, at times keeping people in the hospital past clinical need, and thereby inefficiently using expensive and scarce inpatient services.

• Texas projects focused on improving the mental health and legal system intersections are aligning efforts to decrease the forensic population in hospitals, intercept individuals for treatment referral rather than arrest and prosecution by increasing community-based services. These projects need rapid expansion.

• Developing a roadmap will identify gaps and needs within the mental health and legal systems, leading to pilot programs to create an efficient new ASH care continuum.

• Other models throughout the nation, including the Texas HHSC Forensic Strategic Plan will inform the roadmap.